Road trips are a make or break factor for mass adoption of electric vehicles in the US.

Unlike much of Europe and many other parts of the world, the US does not have a train system that connects most cities in the country. As such, most Americans either fly or rely on their cars when they go on vacation to Disneyland or Disney World, to visit relatives a few states away or take their child to college.

While I have not found an official or agreed upon definition, I’m going to consider a trip of at least 250 miles (at 65 MPH, that is about 3.8 hours in travel time) as a “long trip.” And to qualify or be thought of as a “road trip” is probably in the neighborhood of 500 or more miles.

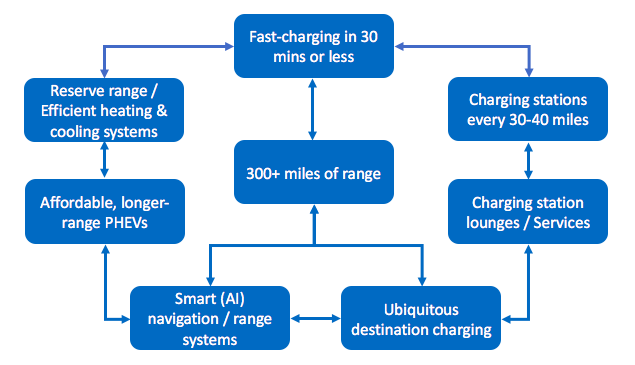

8 Keys for Long Trips to Be a Non-Issue for Mass Consumer Adoption of EVs

Critical to achieving mass adoption of EVs will be to minimize human inconveniences and the need for changes in consumer behavior. The following are 8 keys to help eliminate concerns about long trips among potential future EV buyers:

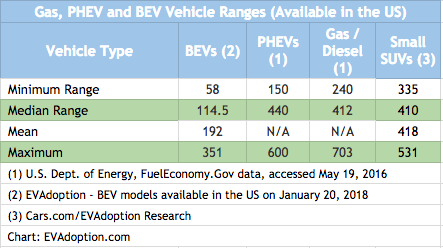

1.~300 miles of range must become the minimum range of future EVs. Quite simply, 300 miles is likely the absolute minimum range needed for most US drivers to be comfortable when taking a long road trip with an EV.

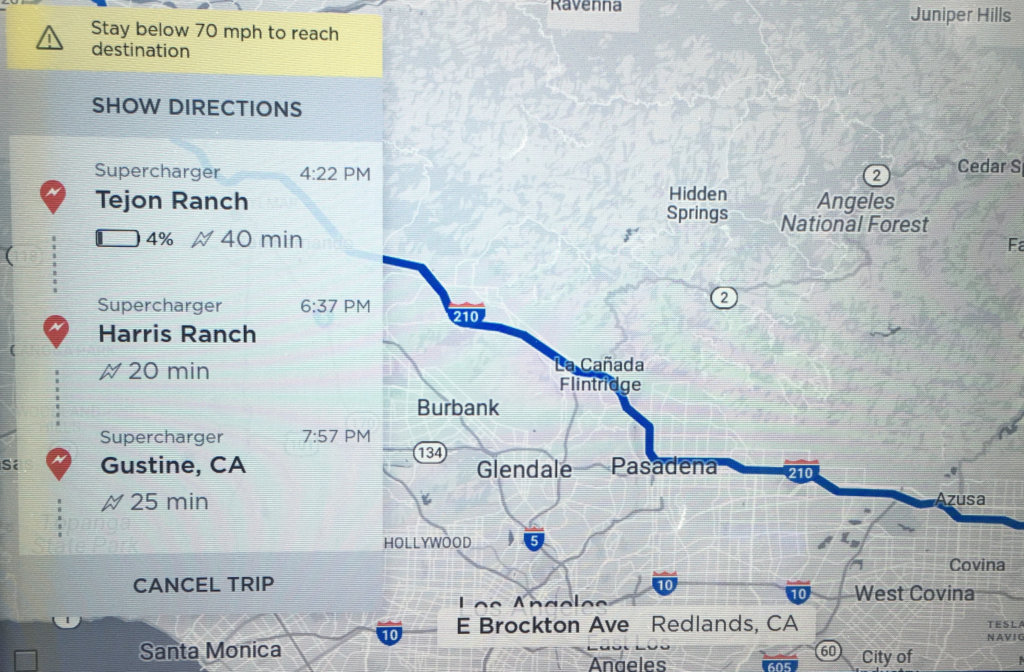

At around 200 miles of battery range in a BEV on long road trips of around 500 miles, you have limited room for error and minimal charging flexibility. Depending on your driving style/speed, weather conditions, charger locations, availability of destination charging upon arrival and other factors – you’ll need to stop and charge at least 3 times, and possibly/probably 4. You also may have to stop at specific charging locations just to ensure you reach your destination with comfortable range to spare.

300 miles of range, however, can reduce the number of charging stops likely to 2 times (one is perhaps possible, but not likely due to the approach of “graze charging” – stopping more frequently for shorter/quicker charges). This longer range and fewer number of needed charging stops is and will be acceptable to early adopters and many in the early majority phase of adoption.

Late adopters and laggards however, will likely require around 450-500 miles of range as American car owners are used to 400-500 miles of range in their ICE vehicles. The good news is that by 2023 I predict the average range of BEVs available in the US will be just under 300 miles. The bad news is that perhaps as many as two-thirds of these EVs will be luxury or specialty vehicles.

Mass adoption won’t begin in the US until there are multiple models in the $25,000-$30,000 price range (without incentives) that also have 300+ miles of range.

2. Fast-charging to a 90%-95% charge in 30 minutes or less (coupled with 300 miles of range): While super fast charging of less than 15 minutes will be critical to achieving mass consumer adoption of EVs, charging to about 90%-95% in around 30 minutes should be acceptable to EV buyers for the next 5-7 years. This comes with a caveat though, which is this charging speed must be combined with about 300 miles of range.

A combination of 300 miles of range and 30 minutes to charge to 95% is likely acceptable for many consumers for two reasons:

A) At an average of 70 MPH, you could drive for about 4 hours – typically about the maximum distance people prefer to drive before needing to use the restroom, stretch their legs and get food and/or a beverage.

B) A typical stop for a combined meal and bathroom break is about 30 minutes (unless you eat in your car) – meaning the moment you are done with your meal your car can also be finished charging.

Longer term, however, for late adopters and laggards to get excited about buying an EV, fast charging on road trips will likely need to be 15 minutes or less.

3. Interstates will need fast chargers every 30-40 miles. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 established the national interstate system in the US. Two years later, according to an article in Slate, the “half-hour” rule of thumb was set out in a policy by the American Association of State Highway Officials. The federal policy outlined that about every half-hour of driving or so there should be a place to take a break – including state-run rest stops, commercial rest stops, and exits to cities.

While I haven’t found any solid data on the average distance between gas stations on highways, anecdotally and except in the most rural areas, it seems that 30-40 miles is a typical distance between gas stations on many US interstates.

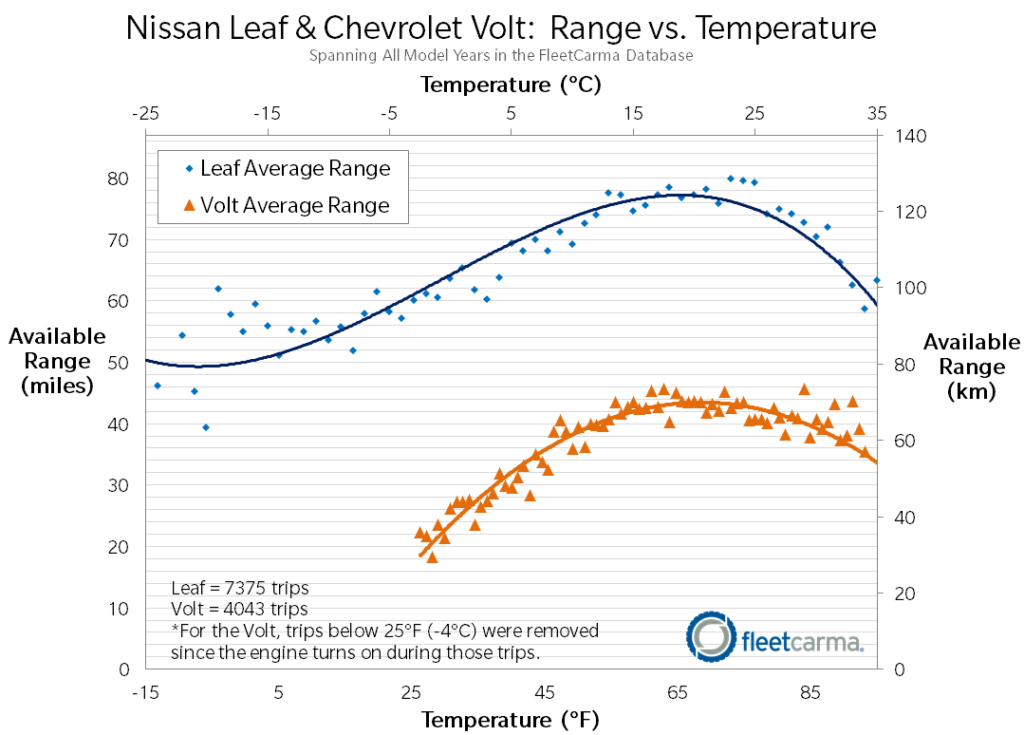

Currently, and for the next several years, EVs most likely to be taken on long road trips will have a minimum range of about 225/250 to 350 miles. Having fast charging stations about every 30-40 miles provides EV drivers with increased flexibility and significantly lessens range anxiety.

Because driving speed, outside temperature and use of A/C or heaters can impact range, knowing that charging stations are spaced every 30-40 miles means that if you miscalculate available battery range, you won’t be too far from the next available charging stations.

Another benefit of fast charging stations located every 30-40 miles is flexibility when one charging location might be full. On a trip down and back up Interstate 5 in California, we stopped in both directions at the Tesla Kettleman City Supercharger. Each time there were only 3 or 4 of 40 stalls in use. But the staff working there informed me that on holidays they’ve reached 35 of the 40 in use at once (and may have reached 40 in use over the Labor Day weekend).

Imagine a year from now when another 100,000+ EVs are purchased in California. Being able to drive past a full charging location and stop at the next one 30 miles away will be critical to reducing EV owner frustration and wait times.

4. Destination Charging Must Become Commonplace. Being able to charge your EV when you reach your destination, such as a hotel or resort, will often enable a driver to stop one fewer time to charge on a long trip. Access to a charging station at your hotel or destination also reduces time and stress trying to find local charging as you know you will be able to charge while sleeping or during down time.

On our recent road trip, because our hotel did not have charging stations, we had to stop to charge for the fourth time shortly before reaching our hotel. We would have reached our hotel in Redlands, CA with about 40 miles of range, but with a drive to my daughter’s college the next morning and then having to drive about 15 miles to the nearest Supercharger, it would have added significant range anxiety, stress and inconvenience.

In the city of Redlands where we stayed, the only hotel with charging stations (including 2 Tesla Destination Chargers) had been booked up for months. But that hotel and most any hotel with Tesla Destination Charging or other EV charging stations will likely always be our (and other EV drivers) first choice of where to stay.

The lesson for hotels, resorts, wineries, ski resorts, theme parks and other destination locations is that in the next few years adding EV charging stations to their property will put them at a distinct competitive advantage over properties without charging stations. For a hotel in 2018, that might mean only 1 or 2 additional rooms booked per night, but in the next few years in high EV adoption markets like California, having charging stations could attract an additional half-dozen or more guests per night.

Beyond the competitive advantage for destination locations, mass consumer adoption of EVs will require the confidence that wherever they travel, there will be adequate availability of reliable Level 2 and DC fast chargers.

Luxury automakers such as Jaguar, Audi, Mercedes-Benz and BMW – all have new BEV SUVs with about 225-300 miles of range coming to market in the next few months to 2 years. These automakers need to steal a play from the Tesla playbook and work with key hotels and resorts in high-adoption EV markets to install Level 2 charging stations.

Secondly, the EV charging networks and station providers (e.g., ChargePoint, EVgo, Electrify America, Clipper Creek, Blink, SemaConnect, etc.) need to educate the hotel industry on the need, value and support of EV charging stations at their locations.

5. Build and run auto club lounges, similar to the airline clubs. Automakers, EVSEs (Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment providers) and food service companies need to step up their game and create a new rest stop model. Even as great as Tesla’s Supercharger network is, the overall charging experience is often not well designed or optimum (the Kettleman City location being an somewhat of an exception, but even it is far from ideal).

The current approach of most charging stations is, and to be fair, expected at this stage of market adoption, to locate them as an add on to available parking spaces. Many are located within easy walking distance of quick-service or fast food restaurants – but it isn’t a stellar experience. This approach is applying an old model to a new technology and infrastructure.

Until super fast charging is a reality and EVs add 200+ miles of range in less than 10 minutes, EV occupants will have anywhere from 10 minutes to more than an hour to multitask while their vehicle charges. The experience and time a driver and passengers spend while waiting for their EV to charge reflects upon the automaker and EV charging provider.

The airlines figured this out years ago with the advent of the airline clubs. While waiting for your flight or connecting flight, they want you to have a great experience. Yes, you might pay $400 a year for access to that airline lounge (or get access via certain credit cards, or airline status) – but the access and experience with these clubs creates a greater “total travel” experience.

Not all automakers will want to go down the lounge rate, nor will some of them need to. But the luxury brands, especially those that broaden their offerings to include mobility and energy (battery storage) solutions will look to these lounges as part of a key strategy to attract and retain loyal customers across multiple product categories.

Some automakers will go the partner route and offer co-branded/co-located solutions with quick-service restaurants, retailers or other specialty service organizations. Auto servicing such as tire rotation, wiper replacement, tire air pressure checks, windshield washer fluid refilling, and detailing/washing/vacuuming are potential opportunities.

6. Use AI and smart navigation to make running out of range almost impossible. Understanding the various factors that affect the range of your EV is something that you mostly learn over time and through trial and error (as I recently learned). But fear of running out of battery range at night on a highway far from home is going to be one of the biggest stumbling blocks to mass EV adoption.

To all but eliminate drivers from running out of battery range (and hence the fear), OEMs should consider the following uses of technology and navigation:

Incorporate contextual training and tips into the navigation system: Driving an EV on a long trip is an unfamiliar experience to travelers – even to many veteran EV drivers who may be used to mostly taking short trips. Automakers and charging companies need to increase education efforts and provide videos and tips for navigating long trips.

EV navigation systems should have smart training systems built in. If you input a trip longer than say 250 miles it might tee up a video and long-trip best practices and tips. (Automotive engineers need to take a cue from software and web interface designers who build in contextual learning and tips into their applications.)

To ensure people actually review the materials the navigation system might require a driver to read a short tip and check a box confirming they read it before it displays the route and charging stops. While this approach might sound heavy handed, automakers must do whatever possible to minimize EVs running out of range – or stories and news coverage will only increase concerns over range anxiety and slow adoption.

AI/Machine learning-based trip planners. Before embarking on a long trip an EV’s navigation and trip (range) planner needs to incorporate factors like the weight of occupants/payload, driving style, weather (wind, rain, temperature), expected use of A/C and heater, preferred locations to stop (nearby restaurants, shopping, etc.), charging stop preferences (fewer stops, for longer times or more stops, but shorter charging times), etc. Secondly, the estimator needs to use machine learning and incorporate the driver’s history and other driver’s real-world range on the same route to accurately predict battery usage for the trip.

Use AI and a voice assistant to keep drivers on top of changes in range estimates: As I discovered on my recent long trip, factors such as steep grades, wind, speed and driving style can significantly decrease range while driving. OEMs needs to incorporate AI and voice-based assistants to alert drivers to changes in range estimates. A sample might be something like:

“Loren, based on current conditions and driving style you will no longer be able to reach your final destination without stopping for an additional charge. If you drop your speed to 65-68 miles per hour your estimated remaining battery range would be 5-8 miles upon arrival. We recommend you now stop at the Emerald City charging station for 10 minutes and add 45 miles of range.”

7. Produce longer -range, price competitive PHEVs: People either seem to love the idea of plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) because of their flexibility and elimination of range anxiety or dislike (hate) them because they still burn fossil fuels and with two powertrains are complex and inefficient. While OEMs continue to produce PHEVs (currently in the US there are 28 PHEVs and 14 BEVs available), only 3 models (Toyota Prius Prime, Chevrolet Volt and Honda Clarity) consistently sell more than 1,000 units per month.

Putting the powertrain and preference issues aside, the other current problems with PHEVs are cost and short battery ranges. Except for the Chevrolet Volt (53 miles all electric range) and Honda Clarity PHEV (47 miles all electric range) most have too short of range, about 15-25 miles (the current median range of PHEVs is 21 miles). Battery ranges of 50-75 miles would make PHEVs capable of handling a large percentage of many drivers’ regular needs, but then they also become incredibly convenient for those few long trips often taken each year.

The second problem is cost differential. As our recent report proved, PHEVs with a high cost delta with the same models with just an internal combustion engine, do not sell well. As the cost of battery packs decline over the next several years, BEVs with 300 miles of range will become more affordable, but so too can PHEVs with 50-75 miles of battery range and 400-500 miles of total range. This flexibility and long total available range will likely be especially attractive to buyers of pickups, large SUVs, and minivans and those without access to home charging.

8. Add “reserve” battery range and efficient systems to run A/C, heaters, and electronics. Consumers have been trained for about 100 years that when their fuel gauge reaches “E” (empty) they still have perhaps another gallon (or more) of fuel remaining in the tank. That buffer is important because although we know that extra fuel is available if needed, the majority of consumers plan their stops at gas stations based on how close they are to the “E” – not the actual total remaining amount of fuel.

EVs on the hand currently have no such buffer. Part of the reason I’m sure is that many BEVs have had battery ranges in the neighborhood of 100 miles or so and artificially lowering that range to say 80 miles would be considered a huge negative.

But as BEVs head toward a minimum of 300 miles of range (and more), artificially reducing range by 20 or so miles to create reserve miles similar to ICE vehicles starts to make sense. To put the control in the hands of the EV owner, OEMs could make the reserve range configurable. If you want 10, 20 or 30 miles of reserve range – or think it is a stupid idea, you can configure to your own preference the amount of reserve range you have available in your range estimator and navigation system.

Secondly, turning on the heater or air conditioning can be a significant draw on the vehicle’s battery and range. And as the use of electronics increases in cars (e.g., navigation and autopilot systems), the battery range can be further taxed. OEMs will need to deliver innovative and efficient cooling and especially heating systems for potential EV buyers who live in parts of the US with extremely cold winters.